About the oil sands

The economic role of the oil sands

October 2024

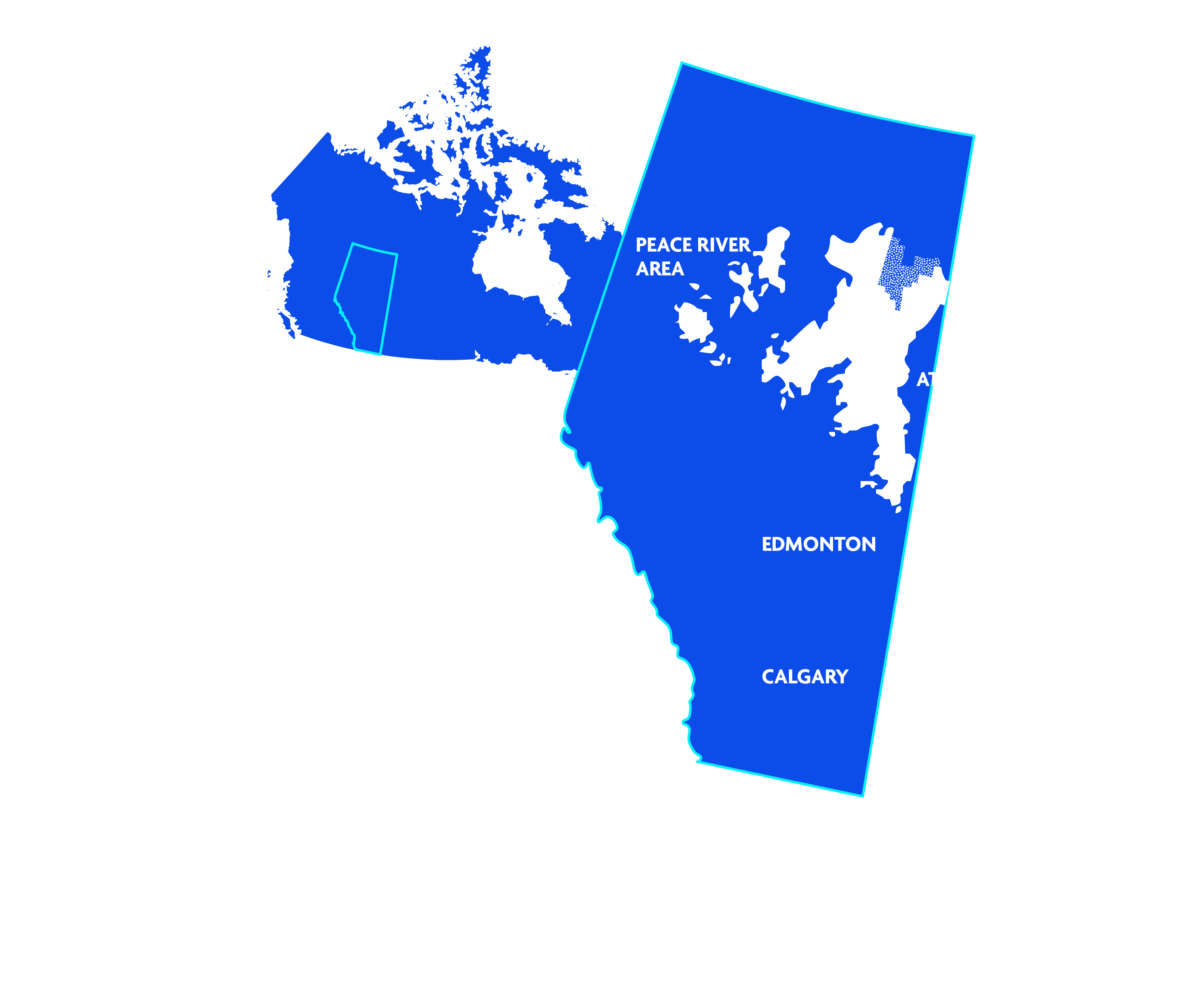

Canada has the fourth largest oil reserves in the world.

As conventional oil production declined at the turn of the century, innovations in oil sands production took some big steps forward. This bitumen resource, which some had dismissed as too impractical, was now commercially viable—and it was a game changer.

Between 2001 and 2023, Canadian production rose by 2.8 million barrels per day¹. Nearly all this growth came from the oil sands. By 2022, Canada’s oil sands yielded 3.1 million barrels per day¹. Today, the oil sands remain an immense economic driver for Canada and Alberta, and a secure source of energy for the world¹.

1Source: S&P Global Commodity Insights, 2023

Alberta has three primary deposit areas:

- Peace River

- Athabasca

- Cold Lake

The origins of the oil sands

People have known about Alberta’s oil sands for hundreds of years—long before these lands were known as Alberta. Indigenous people mixed the heavy oil known as bitumen with spruce gum to waterproof their canoes.

Commercial development of the Alberta oil sands didn’t begin until 1967. That’s largely because the qualities that made bitumen ideal for waterproofing canoes—it’s thick and viscous—make it difficult to get out of the ground.

The facts on bitumen

Alberta has 10% of the world’s oil reserves, mostly bitumen. The low-grade crude oil is so thick that it’s almost solid at room temperature (think cold molasses). To further complicate matters, bitumen occurs naturally in a mixture of sand, clay or other minerals and water. Together, this means that traditional drilling techniques can’t be used to extract bitumen.

The 20th century saw much research into ways to recover bitumen. A breakthrough came in 1929 when Dr. Karl Clark of the University of Alberta received a patent for a separation method using hot water and chemical agents.

The sand, water and clay left from mining operations gets deposited in temporary storage ponds. These tailings ponds allow us to recover the water that’s used in our operations so it can be reused.

Getting bitumen out of the ground

That spirit of innovation later formed the basis for continued technological achievements in the industry. In later years, steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) and cyclic steam stimulation (CSS) , two of the technologies used for in situ (in-place) extraction, were developed. These are crucial technologies because about 80% of the oil sands are deep underground. With both SAGD and CSS, steam is injected into the underground bitumen deposit, heating the bitumen so it becomes less thick and can be pumped to the surface for processing.

Oil sands can also be mined when the deposits are closer to the surface. This is the case in about 20% of Alberta’s oil sands deposits. Mining operations use hydraulic and electric shovels to dig the ore out of the ground. It’s then transported in large haul trucks to a crusher. Once the ore has been reduced to smaller pieces, hot water is used to separate the bitumen from the sand, clay and water. Finally, the bitumen is sent to a treatment plant for processing.

Minimizing impacts

The sand, water and clay left from mining operations get deposited in temporary storage ponds. These tailings ponds allow us to recover process water and reuse it in operations. Once the sand and clay settle in the ponds, they’re stored and used when the land is ready to be reclaimed.

By law, oil sands producers are required to return land to equivalent or greater capability once operations cease.

Our people, their stories

Passionate, dedicated people are behind every innovation and every step forward.